Commonwealthmen (British political writers)

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

Principles of the "early Republicans..."

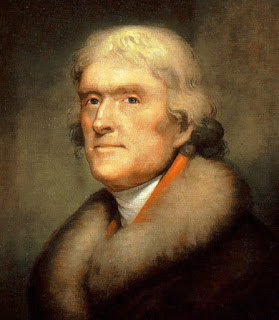

...Those Principles Thomas Jefferson Founded the Republican party on...

Commonwealthmen (British political writers)

By Clement Fatovic

Date: c. 1689 - c. 1790

Commonwealthmen, British political writers of the late-17th and 18th centuries who championed the cause of limited government, individual freedom, and religious toleration following the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89. Inspired by the brief embodiment of these ideals in the English Commonwealth (1649–60), the Commonwealthmen urged constant vigilance against those in power.

The Commonwealthmen drew primarily upon the political ideas of republican writers such as James Harrington, John Milton, Henry Neville, and Algernon Sidney in developing an ideology of protest against concentrations of power in government and in the economy. As a result, they promoted institutional reforms to limit ministerial influence over Parliament, the modification of mercantilist policies, and the protection of individual rights to freedom of speech, thought, and religion, including increased toleration for Dissenters and others. Even though they failed to get many of their reforms adopted, because they never formed an organized party, their ideas had a significant impact on the political thought of the American Revolution, beginning with the Stamp Act crisis of 1765.

Prominent Commonwealthmen in the early 18th century included critics such as John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, who coauthored Cato’s Letters, a widely reprinted set of essays named after the Roman aristocrat who opposed Julius Caesar’s rule. The most-notable Commonwealthmen later in the century included radical philosophers such as Richard Price and Joseph Priestley, the political reformer James Burgh, and the historian Catharine Macaulay. Despite important political, religious, and ideological differences, Commonwealthmen were typically anticlerical writers who warned against the corrupting influence of power and favoured strict adherence to the rule of law and balance in government to safeguard liberty. In many respects, their ideas corresponded to the 17th-century “country” tradition of opposition to the excessive power associated with a corrupt “court” that aimed to keep legislative representatives subservient to the king or his ministers.

The 17th-century English republican James Harrington’s fictionalized Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) was a touchstone for many Commonwealthmen. The most important lessons they took away from Harrington concerned the link between the independence and the liberty of citizens. A strong proponent of the idea that property relations form the basis of political power, Harrington argued that the independence of citizens ultimately depends on their ownership of sufficient land and use of their own arms. In order to prevent tyranny arising from abuses of power or concentrations of wealth, Harrington recommended a balanced, or mixed, government of law, not of men. Inspired by these and other ideas found in Harrington’s work, Commonwealthmen generally opposed the establishment of a standing army; favoured the use of the secret ballot; supported the exclusion of “placemen,” or officeholders dependent on ministerial appointment, from membership in Parliament; and advocated rotation in office, preferably through annual elections.

Commonwealthmen in the early decades of the 18th century advocated many of these reforms in direct response to practices of the newly emerging cabinet government led by England’s first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole. Much like their republican forebears, they were deeply suspicious of executive power and looked to the legislature as the guardian of the people’s liberties. Commonwealthmen in this period decried Walpole’s attempts to extend his influence over Parliament through control over elections, the awarding of government pensions, and the use of patronage as corrupt and unconstitutional intrusions on the independence of the legislature. In their view, liberty was endangered whenever the property or position of an individual depended on the favour of government. Their conception of corruption was not limited to outright attempts at bribery, however. It included any form of interference with the political and economic independence of citizens or their representatives. They urged the people to be ever vigilant against the first signs of corruption and looked to civic virtue as a remedy against the social and political ills afflicting the political system. Writers like Trenchard and Gordon also stressed the importance of definite legal and constitutional rules to limit the powers of government.

The Commonwealthmen’s views on economic and financial matters paralleled their views of politics. They were especially critical of concentrations of wealth and monopolistic enterprises. Some Commonwealthmen favoured agrarian laws to moderate wealth—not necessarily to redistribute property out of egalitarian concerns but to maintain balance out of a concern for independence. There was a fear that excessive luxury would breed indolence in the people and undermine their capacity for virtuous participation in politics.

Commonwealthmen were not necessarily opposed to the development of a modern commercial society, but some expressed reservations about the emergence of new financial instruments associated with the development of the stock market. Most objected to the links that emerged between government and a new class of “stockjobbers” who speculated in public funds and contributed to the growth of the public debt. Implacably opposed to the development of parties, Commonwealthmen warned that these arrangements divided the country into creditors and debtors with divergent interests that undermined the common good. To prevent the further deterioration of virtue associated with these developments, they generally called for cuts in government spending, reduced salaries for public employees, and the end of government pensions.

The legacy of the Commonwealthmen was felt most profoundly in America during the Revolution. People like Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Mercy Otis Warren invoked the ideas of the Commonwealthmen in defense of the rule of law, civic virtue, a citizen militia, frugal government, and the right of resistance against all forms of absolutism. Their influence also helps explain the hostility to party politics characteristic of the early republic.